Would You Invest In Bilbo Or The Hobbit?

December 19, 2012 in Editorial

Imagine for a moment, that you are sitting behind a desk with a large sum of money with which to invest. And imagine that two fellows come into your office and request your financial support for their ventures.

One is a film producer called Peter, who intends to make a movie about a hobbit burgling gold from a dragon.

The other is a hobbit from the Shire, who intends to go to a Lonely Mountain and steal from a fire-breathing lizard.

Who should you invest in?

That depends on how much you have.

The production costs of The Hobbit are estimated to be around $500 million. We are going to assume that eventually The Hobbit will make as much money as The Lord of the Rings did at the box office; the opening weekend of The Hobbit made more than The Fellowship of the Ring, even adjusting for inflation, so this seems reasonable.

With this in mind, The Hobbit will eventually make $2.92 billion. Bearing in mind the $500 million investment, this is a profit of $2.42 billion, and a return on investment of 484% if you choose the movie option.

Then we have the small furry footed chap. His numbers are more difficult to estimate, as very few people these days go on quests for months into foreign places, running into trouble with the residents and hiding from the authorities of that place. (Well, apart from gap year backpackers of course).

Back in the 11th century however, this sort of thing was much more common in the context of the crusades. We got in touch with Andrew Jotischky, Professor of Medieval History at Lancaster University and author of ‘Crusading and the Crusader States’. We asked him how much he thought it would cost to go on a crusade. He said that, based on his reading, the figure of four or five times a knight’s annual income seems right.

With this rather helpful figure in mind, this means that Bilbo’s quest would cost (in modern money) about 5 times the average income of $50,000, or $250,000.

Rather conveniently, Forbes have also published the wealth of Smaug, at the value of $8.6 billion.

Bilbo in his contract is entitled to up to and not exceeding 1/14 of this, or $614,300,000. Which gives a profit of $614,050,000 at a return on investment of 2456%.

So if these two were standing in front of you, who do you give your money to? Well that depends on how much you wish to invest. If you have the capital to spare, then Peter Jackson’s movie will make you a richer man, but for a larger investment. If however you wish to only venture a small amount, then Bilbo offers a greater return on lower up-front costs.

It’s also worth mentioning that Jackson is probably a safer bet than Bilbo. Unlike those who steal from Smaug, your investment in Peter is unlikely to go up in smoke. Or get eaten. Or literally disappear.

And The Hobbit, the novel by J R R Tolkien? The late author is currently earning $12 million per year. Which may be less profit than Bilbo or Peter, but his start up costs would have been minimal.

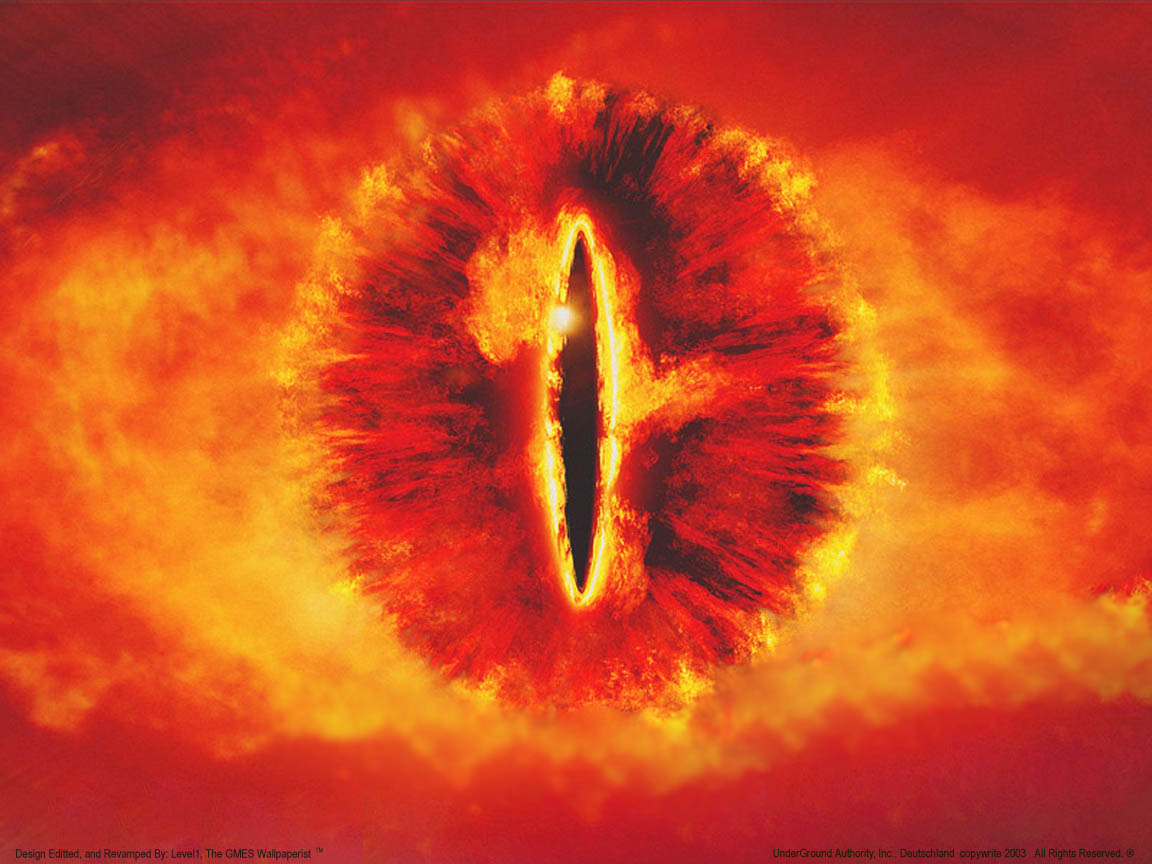

Or, for the investor with vision, there’s always Sauron.

Enjoyed this? Check out our estimate of the cost of sending your kid to Hogwarts, or a look at the Wall That Protects the Seven Kingdoms. You can find this and other articles in our Editorials although for a selection of the best check out our Greatest Hits. And be sure to stay in touch:

It would be easier to invest in Bilbo. You would have to fight off thousands of other potential investors queuing up to provide Peter Jackson with finance for his Hobbit films: by contrast, Bilbo would have a hard time finding any local investors in the Shire (where nobody approves of adventures) or further afield (where everyone is wrapped up in their own concerns). Mind you, the chances of success are much better with Peter.

Actually, this does lead to an intriguing meta-concept: if you failed to invest in Bilbo, he would never go off on his journey. Therefore, Peter Jackson would have no subject matter for his films!

So the greatest problem I have with the calculations is that you are not paying Bilbo. Seeing as he takes a substantial risk, he is due some of the profit from his venture. In addition you are assuming that you must finance the entire quest out of pocket to back Bilbo, and then be only due the 14th share he got at the end. Not to mention the issue of the troll’s treasure, which included for Bilbo a blade of undetermined value. It remains unclear whether you are including the Mithril waistcoat in your calculations of profit. This alone was worth a king’s ransom. If you really wanted to profit off the venture you could take stock in the set up of the lonely mountain once more as a business venture. You must admit that part of the profit of the quest includes any profits earned from the establishment of an entire dwarf mining city, especially considering that all the facilities are already built. The conquest of real estate value must also be addressed. How much land was reclaimed by the quest? How many homes? At present real estate values that alone would be valued in the billions. All this and more should be thought about.

Several fundamental flaws in the analysis here (which for the most part actually strengthen the case, but are worth pointing out in the interests of accuracy.)

1. Gross box office revenues do not accrue in their entirety to the makers of a feature film. Distributors take a substantial cut of the pie; the exact percentage varies from film to film, but a rough rule-of-thumb is that distributors take 50% of the gross revenues before passing the balance back to the filmmakers. Therefore, of the $2.92 billion of gross box off receipts, only $1.46 billion (give or take) will be received by the investors.

2. Studios are notoriously secretive about the production budgets of feature films, so without further information on the source of the $500 million estimate, it’s impossible to judge the accuracy of that number. It seems intuitively in the right ballpark (I’m in the film production business) but could easily have an error of +/- $100 million, which would significantly alter the profitability calculation.

3. The actual production budget is far from the only expense incurred in getting a feature film to screens. Other significant factors which would reduce the revenue stream include, amongst others: advertising costs (often anywhere up to an additional 100% of the production cost), distribution costs (the logistical expense of getting physical and digital prints into the theaters), profit participation for key personnel (directors, producers, writers and actors often receive gross profit participation which comes right off the top of the revenue stream), and residual payments (additional mandated profit participation payable to production personnel in certain unions, such as the Directors Guild of America, the Writers Guild of America, SAG-AFTRA, and IATSE.)

Whilst the forgoing significantly reduce the profitability of a feature film, on the flip side, there are additional revenue streams beyond simple box office receipts, including DVD/BluRay sales, video-on-demand, digital sales (Amazon, iTunes etc.), network television broadcasts, and cable TV broadcasts.) Precise numbers or percentages on these types of revenue streams are almost impossible to get unless you’re an insider at the studio.

As you can see the profitability of a feature film is far more complex than simple box office numbers, and while it’s impossible to calculate the precise profitability of The Hobbit movies without better data, it’s safe to say that the overall profitability is substantially lower than the basic calculation offered in this article.

Yeah but what you have to remember is that the economics of the dark ages were totally different; there was a huge class divide, even bigger than the one we currently have. A knight would have been given a castle and such yes, but that was a one-off payment and would have actually levelled out, especially when compared to how much they had to spend on maintaining their equipment. So sure, $300,000 might be a more accurate figure on their raw income but they would have had to pour a great deal of that back into their job, so I don’t think $50,000 is entirely un-reasonable.

If you are basing this on the fact that we know what the outcome is – ie $2.9 billion and 1/14th share – then you are missing one detail if you have read the book. I won’t put a spoiler on here but if you read the book you can’t calculate Bilbos value. You could guess a value.

I do declare one aspect of your eminent calculations to be bullshit: you say it takes 4-5 times a KNIGHT’s yearly salary to go on a crusade. I won’t quibble with that, since some professor dude came up with it; HOWEVER, you then take that to mean 4-5 times the average salary, $50,000.

Knights were far above average, my friend! If we take $50,000 as the modern equivalent of a medieval peasant’s wages … then the equivalent for a knight would be at least $300,000, maybe even half a milly.

I won’t bother re-jigging the rest of your calculations with this new input.

I took the $50,000 as the average salary of a knight. In the 11th century most people were at the poverty level so $50,000 wouldn’t be the average salary of everybody.